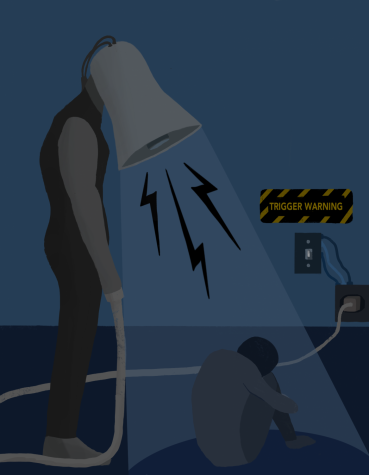

Due to an increase in sexual assault on campuses (or rather an increase in knowledge about these assaults), a culture where parents are expected to become increasingly involved with their children, and the growing sensitivity towards diverse emotional circumstances, the word “trigger” has been used in a meaning different than its traditional one: the button to set off a gun or a causative event. In recent years, the word “trigger” has become closely related to warnings preceding sensitive information and denotes an event that causes emotional damage or, specifically, trauma. This has since caused a wave of controversial debates in higher education about the extent society should extend its sensitivity towards victims of trauma, and how prominent these trigger warnings should be before society ceases to shelter these people for the sake of intellectual freedom or the good of the majority. While critics of trigger warnings may declare them medically pointless, they are hallmarks of our community’s progress in recognizing mental illness’s validity and long-term side effects.

Psychologists analyzing trigger warnings find that if they’re used strictly for avoidance of certain topics, rather than warnings to those sensitive to trauma, the result for healing these victims is counterproductive. “Avoidance of triggers is a symptom of PTSD, not a cure,” and, in fact, exposure therapy is one of the most effective methods of treating PTSD, claims Education Program Coordinator for the Greater Good Science Center Mariah Flynn. Harvard University professor of psychology Dr. Richard McNally states that those who “need a trigger warning… need PTSD treatment.” While McNally and other critics denote trigger warnings as a sign that therapy is needed, the idea that trigger warnings should not substitute professional therapy does not necessarily provide evidence to leave them out of course syllabi. The former, while true, neglects to acknowledge that only properly conducted exposure in a safe environment will help in treating PTSD. Aggressive exposure (or rather an ambush) in a classroom setting is not constructive. Both experts are under the assumption that trigger warnings are meant to replace therapy in affected individuals, when that is not their purpose. The latter analysis also seems problematic on a deeper level, since it implies that those who feel they need trigger warnings should not be able to freely share their mental health

issues or be accomodated, but instead should seek out a counselor privately. This encouragement of staying quiet about issues that already isolate victims is counterproductive to creating a culture where mental health issues are discussed and addressed without shame or secrecy. By invalidating the use of trigger warnings and saying students can just get therapy, critics are ultimately avoiding the issue of how mental illness can drastically affect a victim’s day-to-day life, and how any number of us can feel “triggered.”

From the gross oversimplification that those who feel they need trigger warnings should just get therapy, it seems that the issue of mental and emotional health is still not recognized as a community issue. For example, in freshman literature classrooms at LM, we study how Amir from The Kite Runner copes with the burden of Hassan’s rape and how he seeks to restore his courage. We often discuss these canon works as if they are millions of miles away—it’s easy to do so after generations of English classes have studied them. However, some students do not have the luxury of distancing themselves so far from Hassan and Amir’s experiences. To those who claim that acknowledging this modern parallel infringes upon intellectual freedom in classrooms: can we truly learn what authors wanted us to learn, if we refuse to recognize themes from the novel within our classroom and classmates?

Trigger warnings in the eyes of advocates are seen as a signal for those who have undergone traumatic events to begin to prepare themselves mentally and emotionally. Furthermore, trigger warnings allow everybody to feel validated without revealing their past or anything personal, whether they feel strong waves of emotion towards a particular matter or they don’t. Other than being helpful to victims of trauma, trigger warnings can also say a lot about the society we live in: “Trigger warnings acknowledge the existence of survivors in our midst, address the array of emotional and psychological preparedness students inhabit before immersing themselves in the content of the class, and help to cultivate an environment of care and solidarity,” says Dr. Kirsten Mendoza of the University of Dayton. University of Maryland Women’s Studies professor Dr. Alexis Lothian, explains it is also significant “that the debate about trigger warnings in academia has tended to revolve around sexual content in queer and feminist contexts… [which] might tell us more about the gendered and sexual cultures of campus life than about trigger warnings themselves.”

The discrepancy between those who oppose trigger warnings and those who advocate for them is their intended purpose. While the opposing side asserts that trigger warnings cannot help a victim psychologically, the reality is that trigger warnings are not a replacement of therapy, but rather an acknowledgment of differing mental health states and acceptance of them. Due to the types of trigger warnings that are being targeted by those in high education, this is more indicative of the universities’ “soft flesh” and promotion of “an understanding of sexuality organized through the legal discourses of liability, compliance, and mandated reporting embedded in Title IX,” claims Lothian. The movement for trigger warnings shows a call for recognition of all mental and emotional states in America as well as that victims are often not alone in their experience with trauma: their community stands in solidarity with them.