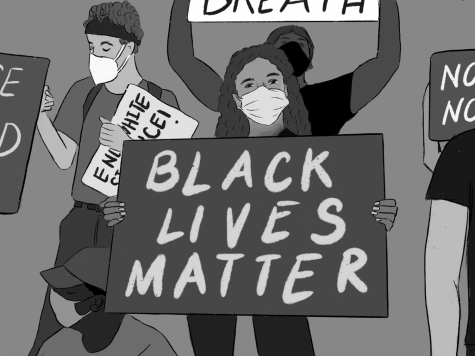

Most students have probably heard of this summer’s local Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests. You’ve seen them on Instagram. You’ve seen the flyers, posts, stories, and speeches. Perhaps you’ve been to one or even all of the events. But why are people out there, really? Why are students protesting in LM when their actions do little to cause real change?

Most people have an intuitive sense of how protesting is supposed to work. You gather a group of people to voice their concerns, and then, somewhere along the line, things change. It seems pretty simple. However, get into the more intricate details of demonstration, and weaknesses reveal themselves. As Zeynep Tufekci from The Atlantic puts it, protests create social pressure by trying to “force a conversation about the topic they’re highlighting.” The presence of a crowd demonstrates that there is an issue that demands attention and discourse. The participation of community members proves that said issue is worth changing policy over. This is why, when the stakes of attending a protest are higher, its effects on the social landscape are usually much more profound and long-lasting.

Taking this into consideration, why does so much of the LM community begin and end their activism with local protest? Have we all collectively done the mental gymnastics to convince ourselves that significant social pressure can be generated when police cars are escorting us down the street? That policy will change when crowds are mobilized with no public demands of any sort? If you look at any of this summer’s local protests, they have been legitimized and supported by the system. Police cars blocking off roads are not necessarily an inherent detriment to a protest but a very obvious sign that you need a change of tactics. If the establishment is already supportive of your activism, there is a need to push harder for concrete change.

Despite the weaknesses of protest in our community, I can’t criticize the social pressure and support that students have been able to bring about. It is undeniable that attending a LM protest is still activism. However, students are still flocking to that specific sort of activism when it does not seem to work.

Our school board and administration have proven to be slow when reacting to social pressure in any capacity. Even with school start times, an issue that was on everyone’s mind, the school board spent years deliberating. In regard to the issue at hand, the district’s ad hoc committee, formed specifically to address racial inequality within our school district, met one time over the summer. 1500 people gathered at Vernon V. Young Memorial Park on June 7–a single meeting over the entire summer.

With everything in mind, members of the LM community need to sit down and reflect on their activism. Ask questions, maybe: “Considering the history of our administration, is protest enough? Is the sacrifice of a weekend afternoon going to create the change I want to see? Does the fact that police officers serve as our escorts have any effect on the strength of our message? If we’re protesting without public, specified demands, are we really being effective? Which specific individuals should we hold accountable for our grievances?”

Perhaps the most important to be asked is, “How do we use the systems around us to our advantage?”

While I’d like to avoid being too critical of the wonderful work that is happening around me, I can’t help but notice that our (predominantly white) community affords the vast majority of its attention to the fun sort of activism. From the banners and posters, to white students chanting “I can’t breathe” and “f*** twelve,” to posts on social media, students seem to be enjoying rather than championing a cause. I can’t help but notice that the most recent protest in our area was organized by non-Black students, despite being explicitly about education inequity, an issue inseparable from race. I can’t help but call these protests “woke parades.”

Looking at everything that is going on, I can’t help but ask, “Are we doing all of this because we want to feel good about ourselves, or do we genuinely not see how ineffective we’re being?”

There are many ways to be an activist, though not many of them are nearly as glory-filled as marching under the sun, a sign clutched to your palms, throat hoarse from screaming. And I understand that showing up to a school board meeting to demand change may not feel as fulfilling as attending a protest. More consistent advocacy can be frustrating, time-consuming, and tiring. But glory is cheap and only lasts for so long. People of color have no appetite for glory if equity isn’t served on the same dish.

If we look back at the issue of school start times, the LM community was able to reach their desired outcome. They harassed (with civility) the board unrelentingly and persisted for months. It seems that this is what it takes. And I know that it can happen. I know that our community can give racial injustice the attention it deserves. Because, if switching schedules around can raise such a fuss from so many people, racial inequity might as well end our suburban dream. Right?