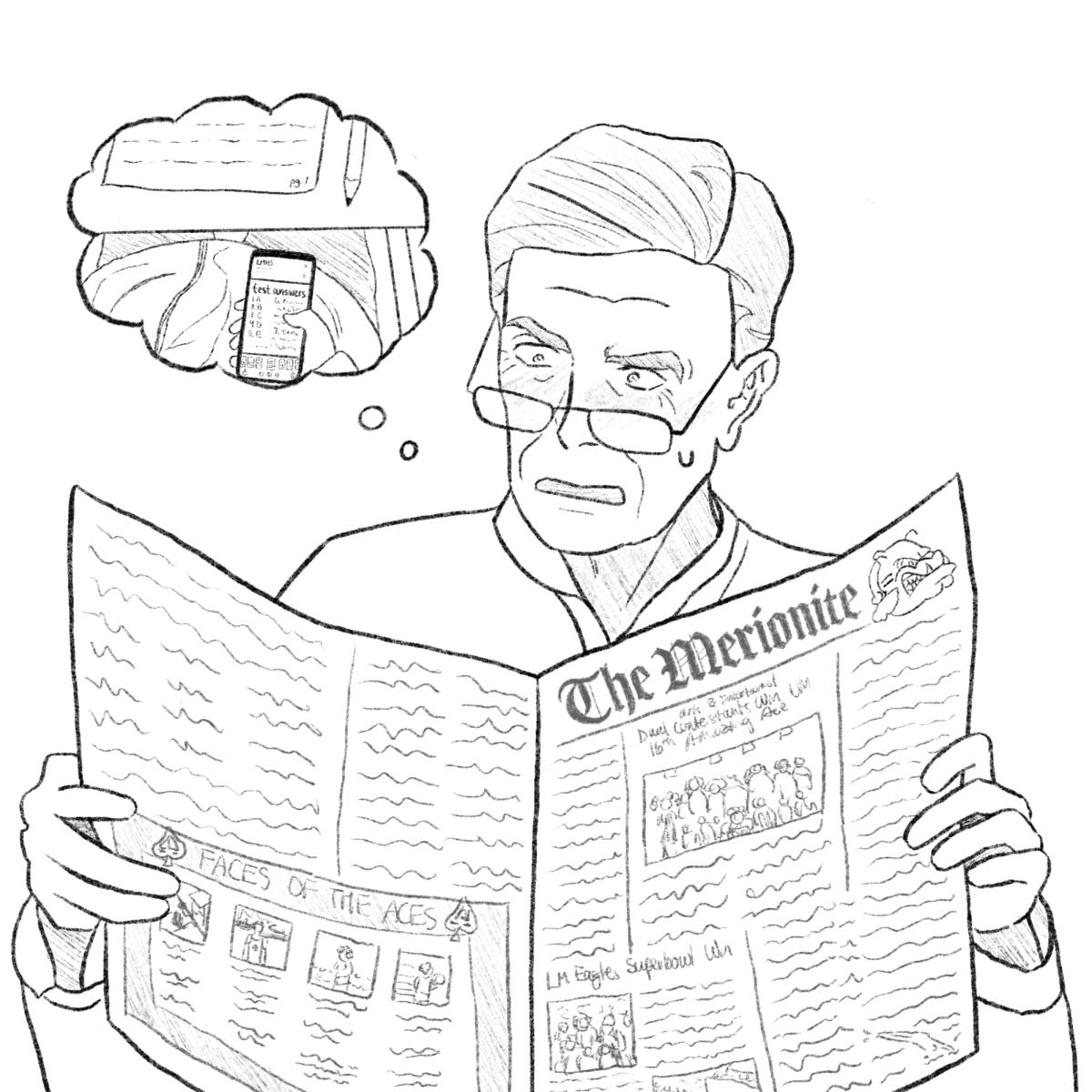

The publication of a recent Merionite article detailing the prevalence of cheating LM has sparked significant conversation among students and teachers, prompting reflection on the school’s academic culture and pressure to succeed. Many teachers were surprised by the extent of cheating described in the article, and some have already begun making changes to their classroom policies.

Biology teacher Jennifer Sand said the content of the article left her feeling frustrated. “I feel like I try so hard to reduce cheating, so to hear how blatant it is—it’s stressful.” She added that she has personally dealt with cheating in her class. Sand has already implemented several preventative measures, including “[spreading] students out so there’s only three per table, [using] test dividers between pairs of students to create barriers, and different test versions as well, so that the questions are shuffled and the answers are shuffled,” she explained. After the article’s publication, she decided to go even further by “[ordering] a set of calculators that can’t store information, just the functions students need, so they can’t store answers or information about the questions.”

Math teacher Kevin Grugan was also struck by how open students were about cheating. “It was just really brazen,” he said, adding that he was surprised by “how [a student who cheated] didn’t regret it. And I just thought it…didn’t feel right from a teaching side.”

Grugan emphasized that his focus is on helping students learn, not catching them. “I’m not the kind to get you on an assessment or ruin your grades or do whatever. I really want you to learn math in my class. I want you to learn how to think. I want you to be confident to ask questions. I want you to be able to handle setbacks,” he said.

In response to the article, Grugan has introduced different test versions and increased monitoring during exams. “As recently as today we had an assessment… I gave two different versions of the assessment during class, and I did it every other row so that students looking to their left or the right wouldn’t see the same version.” He’s also been more vigilant about monitoring students during tests and requiring them to store their phones in the front of the room. Grugan also acknowledged that the article made him reconsider his teaching practices. “I have to probably even be more aware of what I do as a teacher to create genuine opportunities where students are going to communicate to me what they know and what they don’t know,” he reflected.

Grugan, among other teachers, also discussed the article with his classes. “I definitely read the article—different parts that it highlighted—and I talked about it in my set four Precalculus Honors class,” he explained. “Towards the end of one class before Lunch and Learn, I talked about how I thought there were other things that students could consider besides how those students were talking in the paper about what they wanted to do.”

When asked if he thought administration should respond or do something about the cheating matter, Grugan responded by saying, “[LM has] core values; integrity is supposed to be one of them, so the administration needs to reinforce that message,” he said. “It’s not about threatening students with consequences—it’s about building a culture where students feel like they can succeed without cheating.”

History teacher John Grace shared a similar sentiment. He said the article made him reconsider his approach: “If students feel like they have no other option but to cheat, that’s a failure on my part,” he admitted. He added that the article pushed him to reflect on how much pressure he might be contributing, noting that “If I’m adding to that stress, I need to rethink how I’m approaching my classroom.”

Like their teachers, many students also expressed surprise at the caliber of cheating that was described in the article. Yasmin Schmeider ’26 said she was “pretty shocked to hear about the extent to which people went to cheat.” Alex France ’26 noted that the article generated significant discussion among students. “My friends who don’t really talk about The Merionite much were asking me about it. So clearly it generated a lot of interesting discussion.” Tobey Fink ’26 also felt that the article effectively explored a relevant issue at LM. “I thought it was a good article…it had a lot of interesting views on cheating,” he said.

Fink said, “I think that a lot of the time, the motive for cheating is more than just laziness. I think people still study really hard, but if you’re given answers or any advantage, students will take that. I don’t think that’s because they’re lazy, but just because it’s a guarantee it will be correct.”

France agreed that the article’s examples were more extreme than what he’s typically seen, saying “I don’t think the average LM student is going to break into a teacher’s room to steal a test, the article focused heavily on extreme examples, which kind of makes all of the student body seem dishonest.” He added, “I know so many people who work hard and don’t cheat, and I think the article overshadowed that.”

When asked about possible solutions, Grace emphasized that the relationship between students and teachers is important. “If students feel like they have no other option but to cheat, that’s a failure on my part,” he said. “If I’m not paying attention to how much pressure I’m putting on my students, then I’m making their academic experience harder than it needs to be.”

Aliyah Brownstein ’25, the author of the article, said that feedback from teachers has been mixed. “The general consensus I got was that a lot of teachers were surprised. They knew that cheating happened, but they didn’t know how widespread it was. One of the most surprising findings from Brownstein’s research was the extent of cheating on standardized tests like the SAT and AP exams. “The consequences for that are a lot more impactful than just [LM]. Cheating on a test, you’re looking at suspensions or detentions, but cheating on a standardized test, you’re looking at criminal charges, being banned from taking any College Board-administered tests in the future.”

Brownstein said she was shocked that students were willing to take those risks. “If you take an AP exam your sophomore year and you’re caught cheating on that exam, you can be prevented from taking any College Board-administered exams in the future, which means you might not be able to take the SAT or ACT,” she explained.

Some teachers have already started to make changes in response to the article’s findings. Fink mentioned that one of his teachers introduced different variations of tests to make it harder for students to share answers. He also mentioned his AP lang teacher ”mentioned it and gave us an article to read about cheating.”

Brownstein acknowledged that the article has made some students feel uncomfortable: “From what my peers have told me, students are pretty pissed that their cheating methods were exposed. Frankly, I don’t care. The methods themselves were certainly not the central message of the article. Rather, it was to make teachers aware of what happens in their classrooms, and contribute to a culture of academic honesty.” She further adds that students have complained to her that increased teacher scrutiny has made it harder for them to succeed. In response, she says that “If teachers being more aware of how widespread cheating is is making your school day harder and putting more pressure on you, then you’re focusing on the wrong things.”