On March 12, 2025, The Philadelphia Inquirer released an article titled, “Lower Merion led racial equity efforts in the ′90s. But its achievement gap has only widened.” Castigating LM for a racial achievement gap that has not only stagnated but grown, journalist Maddie Hanna shone a light on the enduring inequalities at the school.

The article detailed how the district has prided itself on pushing for racial equity, such as making efforts to close the achievement gap for decades, establishing committees like the Committee to Address Race in Education (CARE) in 1997. However, recent data from the Main Line National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) showed that Black students are underrepresented in AP courses and underperforming on standardized testing. The article included testimonies from Black parents in the district; Some blamed the teachers and administrators for this disparity and others interpreted it as a symptom of a larger issue.

Hanna’s observations took stage against a broader national trend, where students of different races have seen increasingly unequal outcomes in academic performance. While the 1970’s and 80’s saw the achievement gap between white and Black students decrease, the last three decades have held a static and—in some cases—augmented disparity. While Black student performance has still increased since the 1990’s, their advancements have been at a slower rate than their white counterparts.

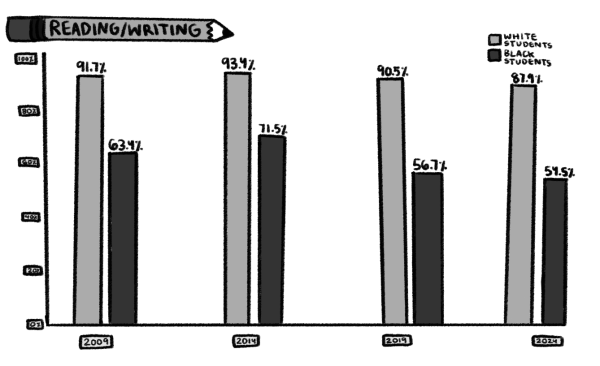

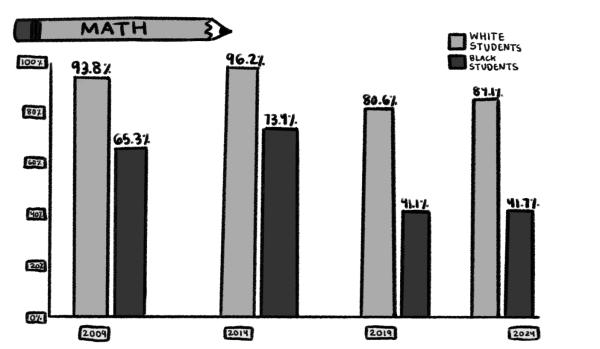

Regarding our district’s achievement gap, the demonstrated disparity in standardized test scores correlates to a similar trend in attendance. According to the Future Ready PA Index, a collection of school progress measures and indicators, persistent daily attendance of white students at LM dropped 5 percentage points (91.8 to 86.7) between 2018 to present day, while Black students have dropped 19 points (83.4 to 64.4). This drop mirrors the Pennsylvania State Standardized Assessment data. In ELA proficiency, white students have dropped half a percentage point since 2018 in comparison to 20 points for Black students. In math, white students have increased by a point, while Black students have dropped 35 points, the last statistic in 2024 recording a 25 percent proficiency.

In response to the article, Interim Superintendent Dr. Larry Mussoline commented that while Hanna included some positive statistics, like Black students’ on-par and exceptional Pennsylvania Value-Added Assessment System (PVAAS) math data, the coverage missed other important values that would also indicate efforts to close the gap. He stated that “[Hanna] failed to include that each year, approximately 80 percent of our Black seniors go on to college, which is an indicator of the overall academic success of our school system.” Additionally, he felt that the article looked at the issue from too small a scope, only focusing on “the experience of just a few families” and the “score gap seen on a single standardized test.” As the School Board cited in their response to Hanna’s interview, “formulating the sole basis of any achievement gap in one standardized test administered at one point in time is flawed.”

As for the LM community, Becton scholars teacher Taj Byrd believes that “as far as suburban districts, mostly white districts go, LM is doing a good job.” When asked about the roots of the achievement gap, he stated that “when people say LM is biased, LM is racist—I used to believe it. Not anymore. That is not the barrier. 100 percent that is not what keeps the achievement gap. Everything is culture.” Going further into this, he explained how this culture is impacting our student body: “I once heard someone speak on the issue and tell me, ‘There’s nothing wrong with young people.’ I couldn’t disagree with that more. There’s something wrong with all of us. We all have deficits. We say ‘the kids are victims’—the kids are not victims. We are only victims of culture.” Byrd’s point of view, while not covered in the article, is likely held by other members within the district. Others, like Georgia Bond ’25, believe that the article did have some valuable and accurate points. Bond details how her biggest takeaway was the voice that “white parents have over the district. Obviously, there are nuances regarding ethnicity and religion, but I think they were accurate to note that the district is more willing to listen to and bend the rules for what white parents want over Black parents.”

It’s clear that this issue has nuances, and many attribute it to different problems in the district. The School Board acknowledged that “looking at [the] data, there is an achievement gap in LMSD, similar to what is seen in nearly every school district in the nation.” Yet Mussoline stated, when asked about possibly reevaluating current district equity policy, that they will “continue to incorporate best practices to support the success of all learners through MTSS (Multi-tiered systems of support) and other practices that give each individual student what they need. Like other strong school systems, we don’t fully understand the underpinnings of this gap, which seems to appear everywhere.”

But while perspectives differ on whether academic inequalities stem from structural or cultural factors, the divides themselves endure. The question of whether the district can—or should—adapt its future equity policies lingers on.