The 2020-21 school year was one of the most difficult to date for everyone. In conversations with more than forty students, teachers, administrators, and parents, taking a look back on this year, it was revealed why certain decisions were made, what people thought of them, and the ramifications they had on the entire community in this uncertain time.

At the end of last year, there was hope that the 2020-21 school year would start with some model of in-person instruction. That sentiment came crashing down on August 5, 2020, when the School Board voted 8-1 to start the year virtually.

Superintendent Robert Copeland, who made the recommendation for a virtual start, said it was not because the school was unprepared for in-person instruction: “By the end of August, the concern was Labor Day…people were going to go away, they weren’t going to socially distance, and there were going to be a lot of cases.”

Shawn Mooring, a School Board member, described his reasoning for voting to keep schools closed because he believed it was not safe yet. “I personally was not completely satisfied with the Health and Safety Plan based on what I understood the risks for spread to be… It was the possibility of exposing our students to a deadly disease that could take out a whole family if things went wrong.”

The vote to keep schools virtual had a lone dissenter, Laurie Actman. “To me, the costs of keeping schools closed were always high, because some students cannot learn at all virtually, some private schools were making plans to remain in-person and because of that, I thought the decision to close schools should be the last resort.” She felt like the proposal was more of a shutdown, as there was no plan presented at that time on when the return to in-person instruction would be.

Overall, students and teachers alike were united in their belief that the decision was smart. “At the time, I definitely was not upset because cases were still bad over the summer,” said Grace McNally ’21. “I thought it was the right decision for us to not go back right away.”

“I thought it was a logical decision,” said Spanish teacher Sean Capkin. “Bringing everyone back at the same time, I thought, would be really challenging… and I didn’t know if we were really ready for it.”

What virtual came best to be known for was its schedule, which students and teachers were fans of. “We backed our way into the best schedule for secondary education,” said Art teacher Russ Loue. He even said he advocated as a department chair to keep the schedule heading into the hybrid model.

The chief concern with virtual learning was that with only three maximum times you could be in a class each week, learning would fall behind. Samuel Davison’s ’21 experience embodied this concern: “It was very hard to stay interested in my schoolwork.”

Teachers had to essentialize their learning to meet these new standards. “I had already clarified my thinking about what was important,” said English teacher Meredith Dyson. “Of course, there is a little bit of stress of ‘are they going to learn enough,’” but she says the fact that everyone was going through this same situation comforted her.

With Labor Day now in the rear view mirror, eager students slowly began returning to the classroom. Whether it was to see friends again, or getting back to normal routines, it was a hopeful sign that maybe things were getting better. “I think one of the primary reasons I went back was because I knew online school was not working for me,” said Jada Goonewardene ’21. “I was in a class with three to four people every day, so I didn’t feel unsafe.”

For teachers, it meant they had to combine their traditional skills of teaching students in-person and their newly acquired knowledge about teaching virtually. “I personally worked a lot to try and integrate technology as seamlessly as possible,” said Spanish teacher Nicolas Severini. That was a way, in his eyes, to make the division between in-person and online students not seem stark.

Hybrid eventually started to hit some roadblocks with functionality issues. Elementary schools had to close temporarily due to increased cases, and then an outbreak amongst the bus drivers forced bussing to pause. Despite concerns, schools remained open during this period. But Copeland described that choice as an error. “It was a mistake. I immediately realized that that had too much of an adverse impact on kids who couldn’t get transportation.”

What this period grew to be infamous for was a rumored bus driver death. Students and teachers alike conversed with each other about the possibility that a bus driver had lost their life to COVID-19. Some parents were especially distressed by these allegations. “The rumor… and the fact the district never put a statement out, was very frustrating to me. The kids all think they know, and the parents don’t know what the truth is,” said Karen Dunleavy, the current Interschool Council (ISC) Speaker Series Coordinator.

Lead Supervisor for School Health and Student Safety Terry Quinlan did say, “We had a staff member die of complications from COVID,” but did not confirm the occupation of this person.

“I think it completely goes against all of their promises of transparency,” said Claire Sun ’21, on the lack of comment by the district. “They should have done a proper yes or no confirmation.”

Administrators have been carefully discussing the situation, not wanting to break medical privacy laws, but Copeland detailed that once the district obtained rapid testing, bus drivers were the first to receive it. He didn’t say it was because of a possible death though, instead explaining that there wasn’t a safe way to ensconce bus drivers in their seats. “Whatever the cause of death was, the bus drivers as a whole were a major concern for the district,” Copeland added.

What came afterwards was a rapid switching back and forth between the hybrid and remote models. Schools went fully virtual around Thanksgiving break, returned to in-person in mid-December, only to go back completely virtual a week later. That return to in-person instruction caused uproar amongst the student body, as case numbers at this point were the worst of the pandemic. This led to more than 2000 community members to sign a petition calling to stay in the remote model.

Copeland said the reason for the quick return back to remote learning was because of a lack of attendance. “The enrollment was so low in the schools that it was becoming difficult.”

said Copeland, describing how he’d react to public pushback to controversial decisions. “At some point you have to say, ‘I’ve heard what people have to say, what medical professionals say, but I think we have to move into a particular direction.’”

The intensity of these debates have been very difficult. “I never would have imagined coming onto the board that my policy decisions would have life or death potential impacts,” said Mooring.

“Everyone was highly emotional, because for the first time we were dealing not only with educational issues but scary public health issues and everyone has an individual approach to how to balance safety and risk for our school community and our own families,” said Actman. “I was personally attacked a number of times…there’s some scars that need to be healed in the community.”

The constant flip-flopping of schedules during this time was difficult for students. Some saw this taking a toll on teachers as well. “I could really see my teachers being frustrated with [the changes], not knowing what direction they were supposed to go,” said Sarah Cooke ’21.

“It never lets you get into a rhythm, and just when you felt like you were getting good at one thing, then it would change,” said Capkin.

During this time, the population of virtual students increased. “A lot of people were switching online,” said Ellie Ward ’21, who made the switch herself. “The teachers started gearing more towards the Zoom classes again, so it was awkward sitting in the classroom.”

A week after winter break, in-person instruction returned, and students slowly began entering the building in greater numbers. “I just got sick of being virtual four days a week,” said McNally.

In March, it was announced the school would be returning to complete in-person instruction, with virtual offerings still available, starting March 22. Megan Shafer, Administrative Assistant to the Superintendent, shortly after the date was announced, explained why it was time to make the move. “Everyone has evolved because we have so much evidence now… Coupled with the downward trends, weather improving in this area, our mitigation measures…We thought this was a time to do that.”

Discussions about returning took place before the teacher vaccination plan started. For some, that was a cause of concern. “It was disheartening,” said Department Head Brian Mays. “Knowing I could still be here with 20 students in a classroom and not be vaccinated is a little disappointing.” He did add though he was pleased to see the district respond quickly when vaccinations became available.

“We had been talking about [a return to full in-person] but we hadn’t yet decided when. And then [teacher vaccinations] got announced,” said Actman, describing the process to get back. “That’s what really catalyzed the back-to-school for us. We obviously want teachers to feel safe when they’re in the building.”

Desks were also moved from six feet distance to just three feet, which came as Montgomery County was still listed as a high-risk-area for COVID-19. However, Amy Buckman, Director of School and Community Relations, stressed that it was within CDC guidelines. “The guidance is six feet ‘to the extent possible.’”

Spring Break also didn’t include a virtual period before or after like Winter and Thanksgiving breaks did, but Copeland explained that now there was less concern that period could be home to ‘super-spreading events.’ “Our positivity and incidence rates were the lowest in the county,” he said. “CHOP was saying there was not a sense of urgency.”

The return to complete in-person was an adjustment. More crowded hallways, packed areas for lunch. It was very different from a school that for months had at a maximum half of its population in it. But the return back at LM hasn’t led to any major outbreaks yet, and students continue to adhere to guidelines, something that earned them praise across the board.

Following the confusion and uncertainty of last year, Principal Sean Hughes said LM administration’s focus was balance. Hughes noted that “patience, flexibility, and understanding” were the guiding principles for their decisions. Over numerous conversations, teachers and students considered that, overall, LM administration did accomplish this.

Teachers faced the unique challenge of having to balance teaching their students, while handling the increased parental responsibility of supporting their own children’s education from home. Over the summer, teachers across the district had the option to commit to teaching the entire year virtually through LMSD@Home, or teach through the uncertainty of changing instructional models. Despite the initial nervous reactions to the district’s mandate that teachers begin in-person, many teachers, like Bill Hawkins, reflected that it “normalized things a bit. When students came back I didn’t feel uncomfortable.” Teacher Jeffrey Cahill added that for him, with three children under nine-years-old, it was difficult to find childcare, but the idea of working at home full-time wasn’t an option either. Nevertheless, he pointed out that LM administration “[has] been incredibly flexible.”

That’s not to say the transition was easy. Special Education teachers, David Clark and Mikell Nigro, were the first to have students return to an optional full-time instruction model. Nigro noted in March she is “still figuring out that balance” between teaching students at home and in school. Special education served as a pilot program for the full-time model that is available now. Clark joined a team of faculty members who provided in-service training for elementary and middle school teachers, which allowed educators to exchange strategies for teaching students in hybrid.

High school students were also given flexibility. With the ever-changing circumstances within Montgomery County and individual students’ preferences, the Board “voted to approve the adjustment of the attendance policy, so that students who wanted to learn virtually without… committing to staying home permanently, had that option,” said Mooring. Throughout months of changing schedules, many students felt similarly to what Ali Dunleavy ’21 put succinctly as,

To ensure safety within the building, LMSD hired disinfectant technicians to support the custodial staff with high-touch areas. “I think knowing that all those touch points were getting addressed…gave another sense of comfort for people starting to return,” said Dennis Witt, the Supervisor for Safety, Security, and Custodians.

A point of great concern for many was how students would eat in school. Quinlan acknowledged “we know sitting without masks on…also at a time that people have the opportunity to be social—it’s just an awful situation.” McNally, who drove to school, said “I walk through the cafeteria, and I’m absolutely horrified. I eat in my car alone every day.” Nevertheless, for many students there were limited options, especially for underclassmen. As it started to get warmer, and students returned to the full in-person model, outdoor options became available.

Outside the regular school hustle, students also had to cope with themselves or family members contracting COVID-19, which hindered the school’s efforts to create a sense of regularity. Over 50 LM students tested positive for COVID-19 this year, as reported by the COVID-19 Dashboard. One student who contracted COVID-19 recounted their experience with trying to continue school while fighting off the virus while they were symptomatic for over six weeks. They were bed-ridden for two weeks as their symptoms changed daily from losing their sense of smell and taste, to chills, body aches, fatigue, and shortness of breath. After reporting their case to both the County and the LMSD, they reached out to their guidance counselor for assistance. “I had to email [them] while I had COVID, which was difficult to muster the strength to do, ” they said, and added that they asked their counselor to inform their teachers about their condition. Unfortunately for privacy reasons, the counselor was unable to inform the teachers.

The student added, “I did not end up telling each teacher because I physically was not able to.” Upon reflection, the student concluded that “I would say I did not receive enough support from the district…I was told there was a plan for me to come back to school, however there was none.”

A teacher, however, who contracted COVID during a school break, shared that they were in frequent contact with school nurses who helped them plan when it would be appropriate to return to school.

Over ten counselors and teachers from multiple departments were asked if they received concrete direction from administration about how to academically support students who were sick. Every single one of them responded they did not. While the idea of flexibility and understanding has been emphasized by both school administration and teachers, the actual implementation has been unclear. Teachers shared that students who felt comfortable enough told them directly that they contracted COVID-19, and crafted plans from there.

From the district administration side, safety was described as the core value guiding their decisions. LMSD struggled to figure out exactly what information and sources to follow in this novel situation. Quinlan explained that “this is the first time that we have not had a lot of direction coming from the federal government, the state department of health, [or] the local department of health…schools have been tasked with becoming public health experts when that’s not their area of expertise.”

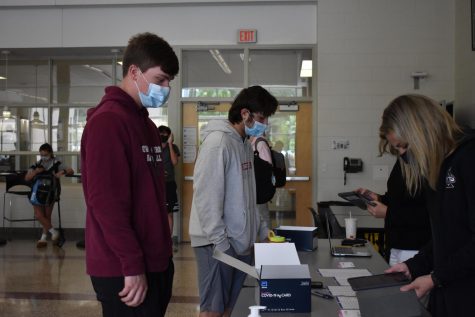

What safety actually looked like manifested itself in many ways, but perhaps the most notable example was Project: ACE-IT, run by the CHOP PolicyLab. This teacher and student testing program used self-administered, rapid tests, which have a lower sensitivity to SARS-CoV-2 than the PCR tests given at some testing centers.

The testing program received praise from participants. Testing gave teachers and students “peace of mind,” a phrase that was relayed constantly throughout interviews. Though, “it was completely voluntary,” Dyson added, “they did encourage, hoping that everyone would participate, and the idea behind it was to catch asymptomatic people.” Witt noted that LMSD goes through 4,400 rapid tests every other week, a feat of the operations and nursing staff.

The nursing staff worked tirelessly to call parents and inform them about exposures and give them support and resources. Teachers and parents received an email every time someone in their building tested positive, but there was no way to know if there were interactions with that person. Students relied on other people to know if one of their peers tested positive, and during the hybrid model there was no notification if a student’s classmate tested positive. With the full in-person model, Quinlan said “you will see more quarantines than you did initially.” The average number of students quarantined are five for elementary school and 44 for middle and high school for each positive case; the highest number ever quarantined was 70 students at BCMS after three students tested positive.

In a year as complicated as this one, communication was essential. In the spring of 2020, on Friday of Memorial Day weekend, the ISC was asked by the District to put together a list of parents/guardians for Copeland to bounce return-to-school scenarios off of at a meeting less than a week away. ISC leaders had little time to put this list together, which soon became “the Committee of Interested Parents,” which was given direct contact with Copeland. At that time, the leaders “didn’t realize this was the actual committee [Copeland] would reconvene over and over again,” explained Caroline Manogue, ISC Co-President. “We assumed that our suggested participants would be supplemented by others in the District and would be just one community input used by the District when making its plan.” Even though providing a safe and productive environment for students was the top priority for parents, teachers, and administrators, there were no student focus groups or representative communication between students and decision-makers outside the few surveys that were sent out before school models were switched.

Despite parents’ frustrations, Karen Dunleavy said, “I don’t know if they could have done better or worse, but I think they worked really hard and did well.” Another LMSD parent said the community was divided, making every decision have its share of critics. “I had to unfollow Facebook groups because it was not helpful to me to read complaints…I feel like the critical voices were really loud…and not always constructive,” she shared.

As the 2020-21 school year began to unfold, after a cancelled spring season, sports made their way back into the forefront of administrator’s minds. Safety was the number one priority when crafting sports’ return. “As long as we could do it safely, we wanted to provide as many activities for students as we could,” said Jason Stroup, the Director of Athletics and Activities for LM.

In September, the Board agreed to the Athletics Health and Safety Plan that formally brought sports back before the end of the month. Many were ecstatic at the news of athletic activities starting up again, but there wasn’t universal agreement. Most notably, players of high-contact sports, such as football, weren’t allowed to begin with other fall athletes due to County recommendations. After public pushback, the Board voted to allow their activities to resume as well.

Those who participated felt a renewed sense of normalcy to their schedules that was previously lacking. “Students now had the opportunity to be in sports programs or different schedules that add to the component of what a typical day looks like,” said Severini, the head coach of the Boys’ Soccer team. “We have a very nice school community, and all those extracurriculars add to it.”

Cooke, a captain of the Girls’ Cross Country team, noted how individual responsibility and leadership was key to her feeling safe. “I had the ability to control the team and our safety precautions,” she said. Even those who practiced indoors felt safe, so long as others around them took the virus equally as seriously. Carmen Cheng ‘21, a member of the Girls’ Volleyball team, specified that her team was “very safe about COVID—six feet apart, we never had our masks down.” From low-contact to high-contact athletes, seldom did students hear about infections on any given sports team, silencing those who believed that reintroducing athletics to LM would cause a spike in cases.

Even with major restrictions in place, there were times where athletes and coaches fell short of following guidelines. Some students were quick to note how the Boys’ and Girls’ Soccer teams were inconsistent with masks and distancing guidelines. “I know that they were just always in these tight packs without masks on,” a student details in regards to the Boys’ team. “We would always get yelled at for not being six feet apart, even when we had our masks on, and no one ever yelled at their team.” There were photos posted on social media by members of both teams, with players and coaches alike standing side-by-side, sometimes without masks.

A member of the Girls’ team mentioned that the degree to which measures were followed varied from person to person. “Some people had their masks on the entire practice, and other people didn’t have their masks on at all, or would just put it up for water breaks. And others just didn’t do anything.”

But the extent of their inconsistencies may not go too far. PIAA guidelines for fall athletics state an important rule: “Athletes are not required to wear face coverings while actively engaged in workouts and competition that prevent the wearing of face coverings, but must wear face coverings when on the sidelines, in the dugout, etc. and anytime 6 feet of social distancing is not possible.” These rules applied to the Central League and LM until November, when masks became required throughout practices and games. Testimonies of both teams didn’t specify when exactly these supposed violations occurred. But the idea of a group being in a tight pack without masks on, or having members of a team seeming to not care about following protocols—even if it’s permissible under state guidelines—is uncomfortable to some.

Nevertheless, Severini recalled that “we followed the protocols with masks, sanitations, spacing, all of those things. Following the protocols helped for it to be a successful season.” And their season was, indeed, a success. There were no reported cases from the Boys’ team throughout the entirety of the fall 2020 season.

More precautions were added for winter sports. After a proposed Health and Safety Plan for winter sports failed to pass in November, the Board approved an updated version by a 7-2 vote. The implemented version included a new program: rapid testing for student-athletes. “The testing was huge,” emphasized Hughes.

With the transition from warmer to colder temperatures, concerns grew over whether or not transmission was more prone to happen with largely indoor practices and games. But students still felt safe in enclosed settings. “My team was routinely getting tested,” said Girls’ Ice Hockey captain Goonewardene. “We were getting negative tests consistently.”

Having a regimented testing protocol meant that students, coaches, and parents knew about cases when they arose. And with tests now in place, there were cases, albeit few and far between. “To call it an outbreak would have been a stretch,” Goonewardene articulated. “We had one positive case.” Students on teams were notified very quickly by school nurses—and by their own teammates—about the cases, reassuring sentiments about the effectiveness of LM’s new system.

Will Treiman ’21, captain of the Boys’ Ice Hockey team, said, “One of the kids [who tested positive] waited a while to tell us, and then waited a while to tell the coaches…By a while I mean a few hours, but a few hours can make a big difference. It pushed back our quarantine three days, so it was a pretty big deal.” The team had two cases throughout the season.

Boys’ Basketball had two as well, when one player and one coach contracted the virus. Davison of the Boys’ Basketball team recounted how his team’s cases almost seemed random. “The coach [had] no idea [how he got it],” he explained. “And the player, my guess, was either from his house or personal life.”

For Ice Hockey, the cases spread differently, as Treiman detailed. “I think the original case was an error of responsibility. Kid told us he was sick the day before, and still showed up. He had his mask off and was close to another kid on the team, who ended up also testing positive.” The initial case is speculated to have come from outside of the rink, but the second case came from inside of it.

Despite these rifts in the system, communication was swift throughout, and no further issues occurred with either team. “[Administration] did a good job limiting the damage,” says Davison.

But throughout all of the successes with athletics, clubs were running entirely virtually for a substantial amount of time. For clubs that heavily relied on in-person interactions, as well as materials largely found on school grounds, it was incredibly challenging to manage.

“It was so difficult, I can’t even begin to describe it,” said Daisy Cunningham ‘21, the Secretary of LM Players. “We had two to three hour zoom meetings every day after school, and they would get nowhere. We just didn’t know what we’d be able to do.” Morale was generally low—especially among seniors—and trying to recruit freshmen into clubs was an arduous task. Players has annual guidelines to fulfill, but with a drastically different year, the Players Board and coaches had to start from scratch.

Emily Shang ‘21 is a leader of a variety of clubs at LM, most of which still garner routine members for each meeting. “We get around 40-50 people each time [for Debate], which is crazy, because we didn’t even get that many people to come last year. People still love debating, even though we haven’t had as much competition this year.” She also noted how Science Olympiad and Mock Trial have both run seamlessly.

Clubs generally had more strict guidelines than sports teams, leading to a fully virtual first semester that most, if not all, clubs had. “We did have to follow what Stroup was telling us, and he was being very accommodating…it was way beyond him. But we definitely didn’t have as many privileges as the sports teams had,” Cunningham noted.

Shang shared a similar sentiment to Cunningham. “It was definitely less of a priority for them. They were in less of a rush to get clubs back. If you weren’t actively seeking it out, they wouldn’t actively want you to be in school.”

Players was fortunate enough to be able to reenter the building for weekly company calls around the start of the second semester, and eventually resumed normal rehearsals. With their livestreamed festival in the works, segments needed to be filmed, and actors weren’t always going to be distanced. Those involved with either unmasked or undistanced segments got tested before their filming dates, just like sports teams.

When asked about if the Players’ company did a good job of following safety rules, Cunningham said that “I think part of the reason why I love Players is because the people in it have common sense. The attitude was: ‘we’re not coming back in unless it’s going to be safe,’ and that was drilled.” She also mentioned that the coaches have done a great job of holding students accountable if distancing wasn’t followed.

Stroup struck down Science Olympiad in-person meetings over the summer, but restrictions slowly began to get lifted. Now, everyone is allowed to meet in-person at school. But this change only occurred right before spring break. Still, all competitions against other schools are entirely virtual. LM finally won the state competition this year, but won’t get the chance to travel for any individual or team national prize. “All of the fun came from traveling and going places,” Shang notes. “Usually I’d be more motivated, because Nationals means that you get to travel with your friends…But this year, it’s all online, so I feel like I’m less motivated.”

While it looks like sports and other extracurricular activities are almost on equal playing fields, it took nearly eight months for the latter to catch up to the former. Stroup articulated that this was largely due to the ability for clubs to remain virtual, as opposed to sports, who heavily rely on in-person practice and competition to craft cohesive teams. But just because something could be done virtually, doesn’t mean that it was ever easy, or even enjoyable. Cunningham recalled, “we would ask ourselves, ‘do we even have to do Players right now?’ The answer was yes. We needed Players because it brought us so much joy, and that’s why we did it in the first place.”

Joy. That’s the underlying factor for so many students that participated in extracurriculars this year. “I definitely don’t regret doing sports,” said Cheng, who was initially going to sit out of her senior volleyball season. “In the end, none of us got COVID. If I had gotten COVID, maybe this answer would be different.” While there was always a chance of contracting COVID-19, the happiness in seeing close friends and participating in cherished activities trumped that concern. Athletes and club members alike attested that if you are truly trying to keep yourself and others around you safe, there should be no reason to not participate in activities this year.

In a year like this one, the district faced a lot of critics for every decision they made. But Sarah Altman, ISC immediate-past president, noted, “Nobody took the day off.”

No matter what personal opinions may have been over specific decisions, many noted that the district worked tirelessly to do what they thought was best. Essentializing the response, Shafer said, “it was about people first… If we could move forward thinking we did right for students, staff… then we could all walk away from the table saying we did the best to meet those objectives.”